Victoria Huffam-Docherty

Wailing like a wounded animal, Victoria crumpled to the worn hardwood floor in the cramped Toronto rooming house because her husband, James, had absconded with their baby to his parent’s home. Temporarily abandoned, Victoria curled into a fetal position, her moans and sobs eventually dissipating into a dazed exhaustion. Upon James’ return, without the baby, tension between the spouses ratcheted up. Victoria wept and pleaded for the return of her child. James lashed out at her, repeatedly striking her body with his fists and blackening both her eyes, swelling them to near blindness. Although the rooming house’s walls were so paper thin that one could hear a neighbour sneeze, and the communal bathroom inevitably displayed evidence of the previous users, no help or intervention by any of the other tenants was forthcoming. As a new immigrant with no friends or family in Canada, Victoria was utterly alone. While not a stranger to hardship and tragedy, this was not what she envisioned of her life when she, as a British war bride, boarded a troopship to Canada two years previously.

Victoria Huffam was born in Rochester, England as the nineteenth century waned, eldest daughter to a former domestic servant and on her father’s side, a deep paternal lineage of marine dredgers who cleared the River Medway ensuring smooth passage of ships into port. Their working class neighbourhood, situated close to the river, was densely populated with the Huffam’s extended family, many involved in the trades of dredging and fishing. Victoria, her parents, and her seven siblings resided in a narrow row house sharing both side walls with neighbours. These two-storey dwellings were architecturally identical with sitting rooms and kitchens located on the ground floor and two bedrooms above. Each room featured one window for natural light and ventilation. Outside, in the modestly-sized back yard, was the outhouse. Every weekday, the Huffam children left their crowded family home and along with their cousins from various uncles and aunts would converge upon the local grammar school to pursue their education and ponder their futures.

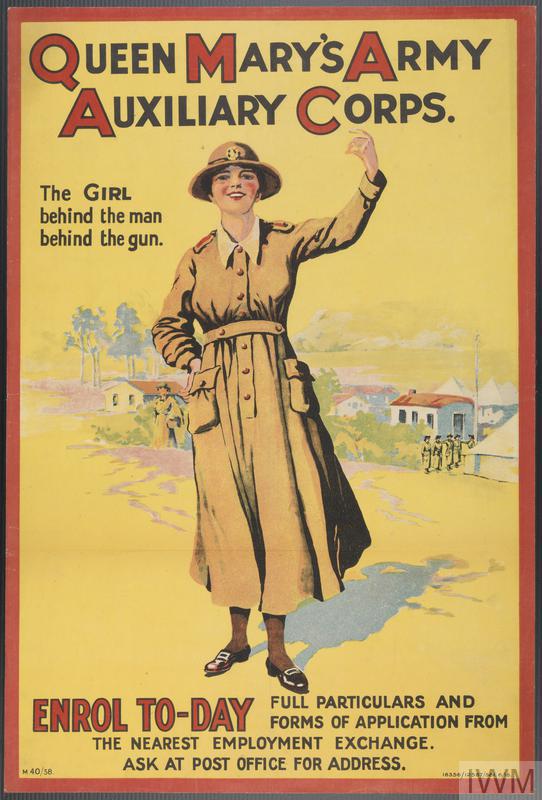

Victoria’s two older brothers had died by 1912, one from a drowning accident and the other, tuberculosis, leaving her as the oldest sibling in the family. Consequently, more responsibility for the family’s welfare was placed on her shoulders. Following in the footsteps of her mother, she procured employment as a domestic servant to supplement the family income. While toiling away with no clear direction for her future, the United Kingdom’s engagement in World War One directly affected Victoria’s life trajectory. Three years in, the British War Office noted the scant number of men available to replace the multitude who were injured or killed on the front lines. Upon review of all military jobs, it was decided that women could supplant non-combative male roles such as cooking, office administrative tasks, and mechanics, freeing up these men for the battlefields. Recruitment posters soon proliferated in 1917 invoking national pride and urgency to help release soldiers to the theatre of war, by urging women to enrol in the WAAC, (Women’s Army Auxiliary Corps), which later was known as Queen Mary’s Army Auxiliary Corps (QMAAC). Victoria Huffam was one of the women who heeded the call to action. She applied to the employment exchange and was required to provide two references, submit to a medical examination, and stand ready to be interviewed before a board of selection. Upon acceptance into the QMAAC, she was outfitted with the official khaki uniform—best described as a no-nonsense, boxy, mid-calf length long-sleeved dress with pointed collar, button front, two large flapped patch pockets on the front of each hip for tucking in sundry items, accessorized with a small round brimmed hat reminiscent of a pith helmet. Victoria received her assignment as a cook at the Woodcote Park Camp in Epsom, just southwest of London. Woodcote was a military convalescent hospital/centre for Canadian soldiers, where she would eventually meet her future husband.

James Docherty, a blond, blue-eyed, slightly taller than average man with a trim build, was the eldest of ten children. As a teenager in 1911, he and his family emigrated from Scotland to Canada, and settled in Toronto. Like many other young Canadian men (and women), James enlisted to be part of the war effort, which led him back overseas to the battlefields in France and in and out of hospitals for both mental and physical injuries. Two years into his service he was diagnosed with peritoneal adhesions, or scar tissue adhering to internal organs due to an appendectomy a year previous to his enlistment. Unable to withstand heavy exertion without excruciating pain, he was found fit for light duty only. Thereafter he served in a desk-bound capacity at various Canadian bases in England. He was transferred to the Woodcote Park Camp in 1918—which was nicknamed “Tin City” due to the sprawling barracks style huts with corrugated tin roofs and walls. Here he settled into closely compacted conditions alongside some three thousand injured and/or diseased Canadian soldiers, and medical, administrative, and support staff. Soldiers assembled for meals in the spacious mess hall, dominated by a wood stove in the centre of the room to best distribute the heat, and furnished with round tables to seat six comfortably, eight if everyone kept their elbows tucked. By 1918, all food was prepared and served by the women of the QMAAC, which resulted in fraternization, in some cases, intimate.

Victoria was the prototypical English rose, naturally attractive with a porcelain complexion and softly flushed cheeks (of which she was extremely proud), and James was smitten. He invited her to accompany him to the camp’s recreation hall for an evening’s entertainment. Propelled by the intense emotions experienced in crisis situations, the whirlwind courtship culminated in a marriage ceremony in Epsom’s Parish Church four months later on an overcast summer’s day. Evidenced by the preponderance of military personnel who married at this church, hastily performed nuptials were not unusual during the last two years of the war.

Concurrent with the armistice announcement on November 11, 1918, scores of women of the QMAAC, including Victoria, were honourably discharged and received a Silver War Badge for their service, each stamped with a unique identifying number on the reverse specific to the honouree. The badge was solid silver with the monogram of GRI for King George V at its centre and the words “For King and Empire Services Rendered” encircling the monogram, and was meant to be pinned to a civilian’s clothes to quietly proclaim their service to the Crown.

Soon after, the Canadian government began arranging passage to Canada for all the “war brides”. This created an awkward situation for the married couple because James had not yet been discharged and was required to remain in service at the Woodcote Park Camp. On the last day of 1918, Victoria was to be one of the 746 civilians (including 284 children under the age of 14), along with 267 soldiers, who were to be berthed on the SS Scandinavian en route to Canada. This 21 year-old trans-Atlantic passenger ship was owned by the Allan Line and had been requisitioned at the outbreak of the war as a troopship, transporting Canadian soldiers to England. After a retrofit in 1912, she could accommodate 400 second-class and 800 third-class passengers, (also known as steerage), on its three decks. Equipped with two masts, she was powered by two steam engines capable of a top speed of 15 knots. Post-war, the SS Scandinavian was shuttling both soldiers and civilians from Britain back to Canada.

(c) Canadian War Museum

On the appointed date, civilians and soldiers huddled together on the Liverpool dock dreaming of their future, eager to board the awaiting steamship to transport them to St. John, New Brunswick, then via the Canadian Pacific Railway (CPR) to their homes in the big cities and small towns scattered across Canada. Cinching coats tightly around their bodies and snugging hats firmly on their heads due to the wind, sleet and slightly above freezing temperatures, the congregated mass murmured and laughed amongst themselves, cautiously optimistic as the Spanish flu pandemic had reached its apex in October and was on the decline. It was New Year’s Eve 1918, and celebrations, not only for their return home but to usher in a new year, were imminent, and high spirits rippled through the crowd.

Victoria patiently shuffled forward in the queue from the dock, proudly wearing her Silver War Badge affixed to her lapel, her excitement building as she slowly ascended the gangway and produced her immigration papers yet again to be checked against the ship’s manifest. Once on-board, her stomach was fluttering not only from this life-altering moment of moving to a new land where she knew no one, but also because she was pregnant.

Directed to her second-class cabin below the main deck, she opened the door to a small room that she was to share with another woman for the duration of the trip. Taking stock of her accommodations, she noted on the right there were two berths (looking rather like bunk-beds) lining the wall, the bedding tightly tucked against the metal half-railing installed to keep the occupants secure during rough weather. To the left was a compact, tufted, fold-down sofa large enough to seat two comfortably. In front of her stood a combination washstand with a basin and a cabinet below to store the wash jug and toiletries, and above, a mirror and shallow shelf to which towels were hooked. The few lavatories and baths, which were shared among the passengers, were located down the corridor. Steerage passengers’ cabins were a deck below second-class, had roughly the same layout but there were either two or four berths per cabin, the washstands plain, and the fold-down sofa functional rather than fashionable. Common areas, lavatories, and baths were austere, cramped, and crowded, barely manageable during fair sailings, and untenable in poor weather.

As the SS Scandinavian set sail for St. John, New Brunswick, no one knew that it would be one of the most noteworthy voyages of soldiers and dependents coming home to Canada. Celebrations for the New Year began in earnest with passengers congregating on the decks and in the common areas, dancing, singing, spreading joy, hope, . . . and a virus. Within the first day of sailing from Liverpool, a female passenger in steerage fell ill with the Spanish flu, a particularly virulent strain of flu known for its ability to cause young, healthy adults to fail. Fourteen cases were noted by the medical officers during the voyage. These resulted in four deaths and subsequent burials at sea, and two more passengers died within a week of docking in St. John. Emergency measures were enacted after the first two deaths on January 8. In an attempt to slow the spread of the virus, all assembly rooms were closed, passengers were forbidden to gather together below decks, other than congregating for meals, and were directed to spend their days on deck in the brisk January air.

Complicating the health of all passengers onboard was six days of intensely violent weather in the North Atlantic, which caused severe seasickness for not only the passengers, but the sailing and medical staff as well. The ship was tossed about amid unrelenting gale-force winds. As it struggled to ride the waves, the bow lifted with the swells and crashed heavily into the troughs. Passengers below decks were rushing to the shared lavatories, projectile vomiting. It was impossible to keep the toilet areas clean, the odour becoming more pungent and sour by the hour, and the floors became both sticky and slick simultaneously. The hospital aboard ship was overcrowded to the point of two women doubling up on each narrow bed; moreover, the assistant medical officer and the two nursing sisters were incapacitated by their own seasickness. It was during this time of extreme weather that passengers were ordered by the captain to remove themselves from their quarters and to hunker down above deck in the freezing temperatures, with winds whipping through their wet and soiled clothing.

Battling six metre (twenty foot) waves, the arrival of the SS Scandinavian was delayed by two days, significant headway being difficult. Finally seeing land, she sailed south of Newfoundland, then followed the southern coastline of Nova Scotia before turning north-east into the Bay of Fundy, finally gaining refuge from the storms. Passengers were greeted by the fog light of the Partridge Island lighthouse, (the island a well-known quarantine station for immigrants of decades past), the beam directing the ship into the proper lane for arrival into St. John, New Brunswick. They docked in the late evening of January 10 to a frigid -16 Celsius (2 degrees Fahrenheit) but were unable to disembark until the civil medical examiners had inspected all passengers. This process took nearly an hour and a half. By midnight, all were cleared to set foot on Canadian soil. Slowly regaining the ability to walk on a non-moving surface, each person firmly gripped the rope railing when descending the gang-plank. Soldiers were diverted to a military-only area while women and children continued directly into the reception hall on the immigration dock to await the next leg of their journey. Also known as the “rest room,” it was equipped with a long row of beds along one side where women were able to lay their children down after the arduous trip. Red Cross nurses managed the small attached “hospital” inundated with women suffering from influenza, seasickness, or both, and the nursery overflowed with mothers washing their babies. Filled to capacity, the bistro-size tables and chairs in the reception hall were at a premium, and in a corner of the hall, tea, milk, and sandwiches were offered for sale. In the midst of this mass of humanity, Young Women’s Christian Association (YWCA) volunteers assembled the women and children as best they could, helping them board the various CPR trains to transport them to their widespread destinations across Canada.

Physically and emotionally depleted from the trans-Atlantic crossing, Victoria Huffam-Docherty boarded the specially-designated CPR troop train bound for Toronto on the afternoon of Saturday, January 11 with the other wives, children, and soldiers. Travellers wended their way down the aisle in their assigned day coaches and settled into the cloth covered bench seating built for two, ensuring the windows were fully shut to protect against the January temperature and climate of Eastern Canada. Most passengers attempted to sleep during the two-day trip, but frequently caught glimpses of Red Cross nurses who moved through the coaches to attend to the health needs of the women and children. On Monday, a bitterly cold January day, the troop train rumbled towards Toronto’s Exhibition Grounds, which had been transformed into a temporary military camp in 1914.

Trepidatious, yet gleefully anticipating her adventure in Canada, Victoria was eager to join her husband’s established, upper middle-class Toronto family. Although bone-weary from the past two weeks of travel, she primped herself up to imminently meet James’ relatives. The train rolled to a stop within the Exhibition Grounds’ gates and passengers were disgorged. The soldiers entered a military building where they would be officially discharged. Underdressed for the well-below-freezing weather and knee-high snow drifts, Victoria alighted onto the platform and was met and introduced to her new father-in-law, James Docherty, Sr., who promptly ushered her away. They drove to a working-class section of the city, and stopped in front of a nondescript, semi-detached, two-storey house. As Victoria and James, Sr. gingerly made their way up the ice and snow-covered pathway and up a handful of stairs onto the porch, Victoria’s excitement deflated. She had been oversold as to the wealth and social standing of her husband’s family. James, Sr. was not a successful banker, as Victoria had been led to believe, but a mediocre stockbroker. She entered the three-bedroom rented home which housed the entire Docherty clan: the father, a heavily pregnant mother, and eight of her husband’s siblings ranging in age from toddler to 18. Living cheek-to-jowl with this many strangers, albeit her in-laws, was not what Victoria was expecting. Adding to the insult was the frosty reception given to her by the family, particularly her mother-in-law. This chilly situation was not unusual for British war brides. There was jealousy from the females due to a new woman in the home, especially one who was pregnant, which tilted the existing equilibrium. While some families greeted their war brides with open arms, others were hostile, cold, and deliberately rude, treating the brides as interlopers. Although Victoria attempted to make the best of it while contending with her burgeoning belly, she quickly became home-sick and heart-sick that her husband was still in England. No family, friends, or close neighbours were there to support her, intervene on her behalf, or for her to confide in. Isolated, she began to feel sorry for herself.

Stress in the home heightened in late March when one of her husband’s brothers returned from the war, debilitated from gunshot wounds in his right arm, hand, and thigh from battles in Passchendaele and Cambrai, and moved back into his parent’s home. Concurrently, a 15 month-old brother succumbed to pneumonia after a week’s illness. A month later, a second brother returned to the family home, although without any physical injuries from his military service. Now there were two more adults in the house and her mother-in-law had recently given birth to another son, adding to the crowded conditions. Victoria, nearing the end of her pregnancy, began to fall into a depressive state, becoming both quarrelsome and withdrawn. By the time James was demobilized and repatriated at the end of June, Victoria had already given birth to a baby girl. The population count in their rented, semi-detached, two-storey, three-bedroom home climbed to 16 people: seven adults, nine children under 18 years of age, including a toddler and two babies.

Victoria experienced a honeymoon period with her husband by her side, but it was short-lived. While James was labouring as a plumber’s trainee, the Docherty clan’s open hostility towards the new mother continued. Unable to withstand the constant belittling and biting criticisms, she soon refused to have meals with her in-laws and began smashing furniture as an outlet for her frustration. Dr. Raymond Ball, a general medical practitioner, was called to the Docherty home in January 1920 by James (and his family) to assess Victoria because she was no longer caring for her appearance nor, according to the family, keeping the house clean. Dr. Ball’s diagnosis and recommendation resulted in Victoria, James, and their baby girl leaving the Docherty family home and moving to a rooming house in downtown Toronto, a three-storey walk-up that housed tenants on the top two floors and a butcher, grocer, and barber occupying the stores at street level.

In their new abode Victoria continued to be despondent. She lost interest in her surroundings, even her daughter no longer brought her joy, and she slept round the clock. She had no energy to take on even the smallest of tasks. Concerned for the welfare of their daughter and without consulting Victoria, one day James whisked the baby away to live and be cared for by his own mother. Realizing her husband had taken her baby from her, Victoria became frantic, her screaming and crying ultimately giving way to debilitating fatigue. Their marriage had strained past the breaking point, and James, upon his return, struck Victoria repeatedly on her body and face. Lying battered on the floor, fury and indignation came bubbling up overriding her depressive state. She retaliated by filing a complaint with the police, and James was arrested for assault and escorted to Toronto’s Don jail. During the next day’s session in Toronto’s police court, James’ lawyer pointedly appealed to all the men assembled, from the magistrate seated on an elevated dais to the reporters in the press gallery, and emphasized James’ patriotic service as a recently returned soldier of the Great War, arguing that he was; therefore, a hero. Victoria, the English war bride, appeared before the magistrate with deep purple bruises on her puffy face. When pressed, Victoria acknowledged she had not made dinner for James in the past month. Unmoved by her facial disfigurement, the magistrate declared James not guilty due to Victoria not upholding her wifely duties; thus finding that James was not responsible for her injuries. Further, the magistrate explicitly blamed Victoria and announced that the couple’s problem lay with her. With very few options available in 1920, especially for a war bride in a new country with no money, no friends, and no family, Victoria returned home with her husband, spiritually broken, withdrawn, and numbingly depressed. Dr. Ball was once again summoned. Victoria pleaded for admission into an asylum as she felt she was insane and needed treatment. It was not unheard of for women, when confronted with abusive spouses and nowhere else to turn, to request admission into an asylum as a respite and safe haven from their husbands. Dr. Ball agreed, and he, along with the psychiatrist Dr. Eric Kent Clarke, son of the famed psychiatrist and asylum superintendent Dr. Charles Kirk Clarke, drew up the requisite two Physician’s Certificates and applied to have Victoria institutionalized in Toronto’s asylum on Queen Street. Maintenance fees of five dollars per week were to be paid by James.

Within the week, on a blustery winter day when chilling wet wind pierced clothing and people instinctively tucked their chins into their collars, Victoria was transported by car along the snow-covered but track-bare brick-paved road of Queen Street, which shared the thoroughfare with Toronto’s streetcar line. Passing by the sprawling University of Toronto’s Trinity College on the north side of the street brought her practically kitty-corner to the asylum. This was an area inundated with both government institutions and sprawling public grounds. Directly to the south of the asylum was the Mercer Reformatory for Females and the Central Prison for Men. South of these custodial institutions was Toronto’s Exhibition Grounds and the Stanley Barracks, where the troop train had rolled into Toronto a little more than a year before and Victoria had stepped down onto the platform to begin her new life. Encircling the asylum was a brick masonry boundary wall approximately five metres high (16 feet), built by male patients in the mid-nineteenth century. It was designed to create a physical barrier between inmates and the surrounding civilians. Inside the wall, on 27 acres, stood an imposing and intimidating structure built four and five storeys high, stretching lengthwise parallel to Queen Street with wings at the two corners extending back towards King Street and the railway. Victoria’s car turned left from Queen Street through the gate opening onto the curved, rutted driveway towards the grand front entrance. She was escorted up the stairs into the main building and on to the women’s admission ward. Here she was bathed, distinguishing marks, scars, and bodily injuries were noted, and was thereafter put to bed. Her clothing was itemized on a pre-printed form, which revealed Victoria was admitted with only the clothing she was wearing plus an extra petticoat and blouse accompanying her.

Courtesy of Toronto Public Library

Once patients were settled in the Toronto asylum, it was expected that each person would engage in some form of traditional gendered labour in the institution; men gardened or performed manual labour while women sewed, knit, laundered, and cleaned. Although not mandatory, the Medical Superintendent promoted these activities to the patients and their families as therapeutic, but what was not openly discussed was this unpaid labour strengthened the asylum’s financial bottom line. Most institutionalized individuals were supported by the province or municipality footing the bill, but there were also patients in the Toronto asylum, including Victoria, who chose not to work because their family was already paying maintenance fees.

Two days after her admission, Victoria was interviewed by one of the in-house psychiatrists, discussing her family history and what had led her to Canada. Victoria was freely open about her life and they segued into why she was presently institutionalized. The psychiatrist observed that Victoria was physically healthy and provided an accurate account of her recent history. Victoria confirmed she had destroyed some furniture and taken her husband to court, and confided that her in-laws were causing trouble for her and that she may be pregnant. However, she was also exhibiting peculiar mannerisms with her face and hands, shifting from vacant expressions to sudden laughter and singing. Victoria was diagnosed with catatonic dementia praecox, an archaic catch-all term defined as early dementia and relabelled later as schizophrenia.

Shortly thereafter, the Inspector of Prisons and Public Charities was notified of Victoria’s diagnosis. Paperwork was initiated to determine if she could be deported back to England due to her mental illness, but before all documents could be completed, Victoria began hemorrhaging, resulting in a miscarriage just one month after being admitted to the asylum. She was placed on bedrest and within a few days it was noted by the doctor that she was quite improved. Upon notification to her husband, James signed a probation bond to have his wife released into his care for two months under specific conditions, including monthly reporting to the Medical Superintendent on her physical and mental health. Failure to report would result in forfeiture of the right for Victoria to be readmitted. James agreed and accompanied his wife back to their rooming house to resume their life together. Although queries were sent from the Superintendent, no reports were ever submitted by James and accordingly, Victoria was officially discharged as “recovered” from the Toronto asylum five months after the probation bond was signed.

Just prior to Christmas of 1920, Victoria was intent on pursuing a case against her husband for insufficient monetary support and she contacted a Toronto lawyer. The lawyer, in turn, consulted Medical Superintendent Harvey Clare of the Toronto asylum and inquired of Victoria’s mental competence. Although the Superintendent claimed that Victoria had recovered from her mental illness, the communications ended with an agreement that rather than legally assist Victoria, it would be prudent to have her deported back to England.

With no lawyers consenting to advocate for her and nowhere else to turn, a heavily pregnant Victoria arrived at the doorstep of the Haven, a temporary shelter of last resort for women who were down on their luck, for those who needed protection, and for unwed mothers, including women like Victoria who had been abandoned by their husbands. Even though the Haven was a charitable institution accommodating approximately 70 women and nearly 40 babies and toddlers, it was run on a highly regimented system. Women rose at 6 a.m., ate breakfast at 7:30, prayed (compulsory), laboured at either household or industrial work in the Haven’s laundry and sewing room (which generated income in order to provide food and shelter for the women), dined at noon, continued with their duties in the afternoon till tea at 6:00 p.m., prayed again, and lights were out by 9:00 p.m. Victoria toiled every day alongside the other women and mothers until the birth of her baby boy. The Haven provided three options to a new mother: one, adoption of the child; two, find a position, usually as a domestic keeping the baby with her; and three, move to the Infant’s Home, another Toronto charity for new mothers and their babies. In Victoria’s case, she rejected all these options, and with her new baby, took the opportunity to move back into the rooming house with her husband.

There were no improvements in the marital situation. After another round of abusive behaviour, Victoria separated from James and acquired a position as a charwoman for general cleaning and housework, likely leaving her son behind with her husband and his family. She was competent in her new position, where she was employed for quite a number of months. However, Victoria travelled to the Niagara area on a holiday with a male acquaintance by whom she subsequently became pregnant, and who declined to acknowledge nor support Victoria or the impending child. Unemployed (and probably homeless) due to her condition, options for Victoria were scarce. Some Unwed Mother’s homes in Toronto refused admission to women who had previously availed themselves of assistance and had become pregnant once again. Moral thought was the first pregnancy could be an accident and the mother could be “saved,” but not subsequent pregnancies. Victoria ultimately contacted Dr. Eric Kent Clarke, the same psychiatrist who had provided an appraisal for her first admission into the Toronto asylum, and he, along with Dr. G.W. Anderson, examined Victoria. They noted her marked mental deterioration and that she had contemplated suicide, was careless in her dress, apathetic, and particularly the fact that she was willing to return to England. Doctors Clarke and Anderson completed and submitted Physician’s Certificates to have Victoria once again institutionalized in the Toronto asylum at the maintenance rate of $5 per week to be paid by her husband, James.

Victoria was re-admitted into the institution the summer of 1922, one of 556 patients who entered that year. She was led to the new bathing facilities, upgraded since her last admission with freshly tiled rooms and the most modern and up-to-date fixtures, including toilets and tubs. She removed her clothes (the only clothing she had arrived with), in preparation for the obligatory admissions bath. In addition to her one enamel brooch and wedding ring, it was observed that her underclothes, dress, coat, hat, and shoes were all in poor condition although clean. Afterwards, she was fed and sent to bed to rest. A couple of days later she met with Dr. Robert Dudley Blott and Dr. Fulton Schuyler Vrooman for a physical and mental examination, and to gather her recent history. Coincidentally, Dr. Blott was a young doctor who was invalided from the war due to gun shot wounds at Ypres, and had convalesced for a time at the Woodcote Camp in Epsom, a couple of years before Victoria made her appearance. It is unknown whether they knew of their shared geographical history. Post-examination, Dr. Blott claimed Victoria’s judgment was good, although Dr. Vrooman contrarily remarked she was lacking in judgment. No further notations were written in Victoria’s case file until the end of December when she gave birth to a baby girl who, when old enough, was expected to travel with her mother to England upon deportation. Observations were documented regarding Victoria’s attractiveness and detailed the facial exercises she performed to maintain her fresh complexion, along with the fact that she had no delusions nor hallucinations but her dementia was rapidly deepening. Victoria was experiencing postpartum issues, specifically irritability, fatigue, and an insufficient secretion of milk. Dr. Vrooman unilaterally decided to have another patient wet nurse Victoria’s infant. Quoting from his notes in Victoria’s case file, “I decided to have the baby nursed by the Negro woman, Mrs. L___. [. . .] Mrs. L___ nurses the child somewhat reluctantly, and if it does not do well, we will have to resort to artificial feeding by the bottle.” This situation resulted in sharp jealousy on Victoria’s part, watching another woman breast feed her infant, and as a consequence, Victoria was transferred to another ward away from her baby. She had now been “relieved” of her third child.

At the direction of the Medical Superintendents of the Toronto and Cobourg asylums, Victoria was among the two dozen “quieter” women in good health who, in February 1923, were transferred by rail from the Toronto asylum to the Ontario Hospital, Cobourg, located over 100 km east of Toronto in a small town on Lake Ontario. Concurrently, Dr. Vrooman wrote to James, Victoria’s husband, informing him of her transfer and inquiring as to who would be taking custody of the baby girl because Victoria’s daughter was not being transferred with her. But James was no longer living in the rooming house. It wasn’t until a few days later that the hospital administration was able to track him down to his parent’s new home where he had been living for months. There was no response from James to the Medical Superintendent’s letters, and it is likely Victoria’s infant daughter was put up for adoption.

Toronto Star Photograph Archive, Courtesy of Toronto Public Library

Meanwhile, with temperatures hovering just below freezing and a light snow floating down with barely a wind, Victoria arrived with the other patients in Cobourg. They were transported en masse from the train station and driven up the snow-covered hill to the asylum’s outdoor stairs to ascend to their new home. This hospital was more humble in size than the Toronto asylum, housing slightly less than 400 women, but had an air of sophistication with its light-coloured brick and symmetrical wings running parallel to the road. Four neoclassical columns, each three stories high, flanked the centre-located outdoor stairway, and a prominent cupola graced the centre roof. Its aesthetics did not feel as intimidating and institutional, perhaps because the building was originally erected in the mid-1800s as an educational academy, later to become Victoria College University until it merged with the University of Toronto. It closed its Cobourg doors to academia in 1892. A decade later, the Ontario Hospital, Cobourg, was inaugurated as the province’s sole women-only facility. (All asylums in 1919 were renamed Ontario Hospitals to help remove the “asylum” stigma.)

Like the Toronto asylum, patients were expected to contribute to the hospital’s maintenance according to their abilities. Options included helping prepare the meals or waiting tables in the dining room, cleaning and polishing, washing endless bed linens, towels, and patient clothing, or, for the very privileged few, assisting with office work. Victoria laboured diligently in the hospital’s front office each day. Staff acknowledged she was clever, cheerful, and gave no trouble. On a routine day when patients and staff alike were relaxed in the warmth of summer, with windows wide open to capture the fresh breeze drifting in from Lake Ontario, Victoria was summoned by her first name, an insult of over-familiarity of which she took great offence. She responded by refusing to engage in any further work. Victoria was soon thereafter diagnosed with dementia praecox, paranoid, the same catch-all diagnosis she was labelled with in 1920.

At the turn of the new year in 1924, four years after the first discussion of Victoria’s deportation, the Department of Immigration and Colonization contacted Dr. Vrooman at the Toronto asylum requesting Victoria’s particulars, including whether her maintenance expenses ($5 per week from husband James) were ever received. The asylum’s bursar verified that no maintenance had ever been paid by James towards Victoria’s second institutionalization. Then there was silence from the Department while Victoria languished in the Cobourg asylum, becoming ever more despondent. Eventually arrangements were made for Victoria to return to England in the summer of 1925. She was uplifted and amenable to the idea, but for an inexplicable reason the deportation was halted. Victoria’s spirits deteriorated even further due to this deportation limbo and she lost her appetite, losing flesh and becoming weaker. By mid-1926, the doctors noted she was emotionally dejected, although rational and sane. Physically, however, they had diagnosed a possible issue with one lung. In the fall, Victoria’s deportation was arranged yet again. A female officer arrived at the Cobourg asylum to escort her on the two-day train trip to New Brunswick, ensuring Victoria’s attendance on the ship taking her back to England and her father. At the vaguely familiar dock in St. John, Victoria ascended the gangplank to the steamer alone, forever leaving her three children and husband behind.

This voyage was sparsely populated, with none of the energy and shared hopefulness of her previous trans-Atlantic sailing. There were less than 50 passengers in first-class cabins that could comfortably accommodate 500, and the percentage in third-class, previously known as steerage, was approximately the same, just over 100 individuals in an area that could hold 1200. Most were travelling alone, no spouses or children accompanying them. Quite unlike the troopships during World War One, aesthetics of Canadian Pacific Ocean Service ships post-war were designed to mimic an upscale home atmosphere replete with mouldings on walls and ceilings, comfortable wingback chairs in the drawing rooms, and linen tablecloths with floral centrepieces in the dining saloon rather than the nautical architecture of years past. Dinner options in first class included halibut with hollandaise sauce, curried lobster, or roast chicken, with grilled tomatoes and boiled potatoes on the side, and wine was available to round out the meal. However, this time, Victoria was not sailing in the upscale cabins, she was travelling in third-class with its basic ambience and food.

After a frigid north-Atlantic crossing in December, the ship docked in Southampton on the south coast of England amidst heavy fog. Victoria, underweight, coughing, experiencing chest discomfort and fatigue, disembarked the ship into the waiting arms of her father (her mother having died during the war) who transported her back to her hometown on the east coast of England. They arrived at her father’s cramped, three-storey, russet-brick terraced home near the River Medway, where Victoria’s three brothers and two sisters were waiting to greet her. Christmas was a mixed blessing that year as the family was together, but Victoria was suffering. By the new year, she was feverish, losing even more weight, in pain when she breathed, too exhausted to rise from her bed, and had begun coughing up blood. Her father recognized the symptoms of pulmonary tuberculosis, remembering the fate of his late eldest son. Unable to care for her in this state, Victoria’s father admitted her to the infirmary at the Magpie Hall Lane Workhouse, administered by the Medway Poor Law Union’s board of governors.

The infirmary, a long, squat, two-storey brick unadorned structure, was hidden from immediate view of the road and set off independent from the main workhouse, tucked in slightly to the left and behind. Victoria and her father wound their way along the driveway to the infirmary’s administrative building, then slowly up the dozen or so stone steps into the entrance hall. Victoria was admitted and removed straightaway to the women’s section of the infirmary where the sounds of guttural coughing, anguished groans of pain from patients no longer able to stay silent, and the underlying mingled scents of urine and bleach welcomed her. For a number of weeks she resided in close proximity to other impoverished women with influenza, broncho-pneumonia, senile decay, tuberculosis, and cancer, until the doctors deemed her healthy enough, not cured, but healthy enough, to be transferred into the actual workhouse.

Workhouses were refuges for the destitute, although refuge in its barest meaning. (Stigmatizing) institutional clothing was provided to each inmate and a strict routine of rising, eating, working, and sleeping were regulated according to a time table. Inhospitable surroundings were created to encourage the inmate to discharge themselves, but many were not physically or mentally able to do so due to age or infirmity. Shelter was rudimentary, food was adequate at best, and all inmates were expected to work, including the elderly and infirm. Victoria’s father, upon hearing of her transfer into the workhouse, demanded she be released into his care. She departed the institution within four days.

Back at home, Victoria’s father ministered to her as best he could, but he despairingly acknowledged a few months later that Victoria was failing rapidly and needed to be cared for by competent medical staff. She was once again admitted to the Magpie Hall Lane infirmary where the doctors and nurses realized Victoria was exhibiting signs of impending death. In a state of unconsciousness, Victoria took her last strained breath with her father by her bedside, and passed away from pulmonary tuberculosis at the age of 30. She was quietly laid to rest in the family plot. It is unknown whether Victoria’s estranged husband and family were ever notified of her death.

Victoria Huffam-Docherty is a pseudonym and parts of her story had to remain vague to respect privacy and my agreement with the Archives of Ontario. But “Victoria” was indeed one of many women who were British war brides transplanted into Canada after World War One. While many thrived in their new homeland with loving husbands, children, and extended families, and some returned to England of their own volition realizing life in Canada was not for them, it is difficult to conceive of war brides institutionalized in an asylum. Due to limited access to Ontario asylum case files because of privacy constraints, we will likely never know just how many British war brides endured the same heart-breaking fate as Victoria.