Emily Metcalf

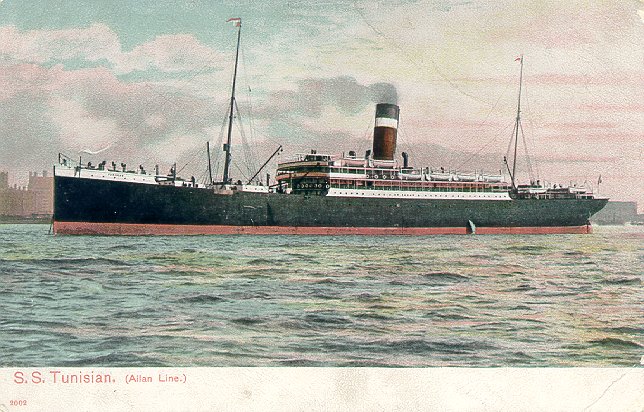

Excitedly squeezing her older sister Elizabeth’s hand, Emily was awestruck at the sight of the S.S. Tunisian, the ship that would sail them and the other British Home Children to start life afresh in Canada, wiping away her troubles over the last decade. She had persevered through family illnesses and deaths, forced estrangement of siblings, homelessness, and an arrest, all before the age of 15. From her perspective, life and opportunities could only get better.

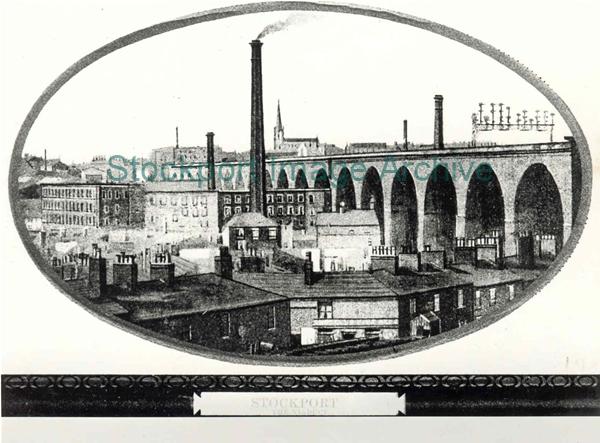

Living beneath the Stockport railway viaduct, everyone had become accustomed to the constant bass rumbling of the trains traversing the River Mersey Valley. Broad shadows were cast below by the physically and visually imposing bridge’s red-brick arches over rows upon rows of workers’ cottages in this industrial town where the Metcalf family had lived for half a century.

It was here where Mary Metcalf gave birth to her seventh child, Emily, in the late 1800s, although she was only the fourth child to survive. Survival under adverse conditions was baked into Emily’s nature. Her father, William, a brass moulder in an iron foundry, worked back-breaking ten to twelve hour days in a physically demanding and stifling environment. Her mother was employed in Stockport’s main industry of cotton manufacturing, breathing in cotton dust day after day while controlling the machine that combed and aligned the fibres. It was a hard-scrabble life that was about to get worse. In 1903, William suffered from extreme fatigue and rapidly lost weight from his muscled frame. With another child on the way, William forced himself to continue working through his pain and exhaustion. A few months after his daughter, Leah, was born, he passed away from Addison’s disease.

William’s untimely death caused turmoil within the family that would reverberate through the rest of their lives. Emily’s oldest brother, also named William, a young lad of 14, took over as the “man” of the family and toiled in one of Stockport’s mills to help keep food on the table and a roof over the family’s head. He cared for and lived with his mother till her dying days. Elizabeth, Emily’s older sister, and only about 10 years old herself, was sent to an Industrial Training School, a charitable organization for destitute or orphan girls, to be educated in domestic services. As a young teenager she acquired a live-in domestic servant position, employed by a cotton mill executive to tend to him, his wife, and their young daughter at their spacious Victorian home. The Training School kept in touch with Elizabeth, not only to provide emotional support, but also to record the success or failure of her employment. Leah, the newborn, was boarded out as a pauper child to a foster family, never to return to her mother. Emily remained at home with her mother, brother William, and another older brother, James, a small boy in both height and weight suggesting a few years younger than his age of eleven. In rapid succession, the Metcalf family unit had decreased to almost half of what it was, and what was left was crumbling. James began drifting away from the family, not attending school, not working, just spending time on the streets, coping with the losses in his own way. That is, however, until he was just shy of 13, when he was apprehended by the local constabulary and placed in a boy’s reformatory for habitually wandering. Although he was to be detained until the age of 16, after two years he was sent to Wales as a farm labourer under the supervision and authority of the reformatory. Emily, seemingly not provided with much guidance, care, or attention after the dissolution of the family, felt she had to fend for herself. Following in James’ footsteps and still a young girl, she began begging on the streets until she was taken into custody as a vagrant. The authorities decided that she be sent to a Children’s Industrial Home to be trained in the art of domestic service, in keeping with her station in life. Following their father’s death, the Metcalf children had been torn apart. Less than a decade later, the Metcalfs had permanently dispersed. James and Leah were estranged from the rest of the family. William had recently married and started his own brood. Mary, the mother, cohabited with William and his new wife until Mary, at the age of 44, succumbed to cardiac disease and bronchitis in 1911, possibly accelerated due to working with cotton fibres for years. Elizabeth was labouring as a live-in domestic servant and Emily was an inmate of a Children’s Industrial Home. However, a few months after Mary passed away, an opportunity arose for the sisters to emigrate to Canada via the British Home Child scheme.

Although orphans from the United Kingdom had been transported to Canada from the early 1800s, the programs began gaining momentum after the confederation of Canada in 1867. Childrens’ Homes in mid-nineteenth century UK were bursting at the seams due to the admissions of “street children” and loosely-categorized orphans, including children with at least one parent, but living in desperate poverty or workhouses, or who had been abandoned. Alternative measures were necessary to expand the child-saving mission. Emigration of these “waifs and strays” to other countries of the Empire, but most conveniently, Canada, helped solve the economic problem of overcrowding and threat to society’s good order in the UK while providing cheap domestic services and farm labour for residents of Canada. There was hope that these children would be enveloped into the bosom of families and pursue better, happier lives in rural Canada with fresh air to breathe and wide open spaces, rather than stagnate in poorhouses or slums of the UK’s big cities with its foul air and petty crimes.

Most British Home Children presented for emigration in the early twentieth century were aged 8 to 14. Elizabeth Metcalf, at age 17, was at the uppermost limit to be included among this group. Furthermore, she was already in service as a domestic. Usually organizations did not remove a working “child” from their position for immigration purposes, unless perhaps Elizabeth was between jobs or was in moral jeopardy. It is possible that Emily, a young teenager living in the Children’s Industrial Home, was induced to emigrate with the promise of Elizabeth accompanying her so they could start a new life together in Canada, or, perhaps Emily flat-out refused to emigrate without Elizabeth. Regardless of how it came to be, Elizabeth and Emily were chosen to be part of Dr. Thomas Barnardo’s group to immigrate to Canada. Over 125 girls and almost 200 boys, many pre-teens and young teenagers, were plucked from various Industrial Homes and foster homes across England where the children had been boarded-out, to be transported via train to Liverpool. On June 14, 1912, over 300 children were crowded together on the Princes Landing Stage/dock in Liverpool, acutely aware that it was exactly two months to the day after the sinking of the Titanic; the inquiry making front page news in newspapers on both sides of the Atlantic, and adults nearby quietly conversing about the subject. Clutching tote bags full of their worldly possessions, they momentarily stood motionless with unblinking eyes, chins inclined and mouths softly open, awestruck at the S.S. Tunisian’s expansive black hull with a red stripe above the water line. Mid-ship, the striped black, white, and red funnel belched swirling smoke in preparation for sailing on this temperate day, and the two masts, both port and stern, were ready to deploy their sails when needed.

Regaining their composure, the children awaited permission from Alfred de Brissac Owen, the Canadian representative of the Dr. Barnardo organization, and the six other adult chaperones, to embark the S.S. Tunisian and sail away to their new lives in Canada. After much paperwork in which some female immigrants were recorded twice in the official ship’s manifest, the Home Children filed, some hesitatingly, some eagerly, onto the ship that could accommodate almost 1500 passengers, including 1000 in third class (steerage). All the children were situated in steerage, the lowest of the four decks and closest to the water, and were separated according to gender for the purposes of eating, sleeping, and hygiene. Over the next nine days while the ship crossed the north Atlantic, there were tears of apprehension, homesickness, illness, discomfort, and loneliness to accompany the children on their travels. Even for those who wished to eat and were not suffering from the movements of the ship, food may not have been plentiful. On Sunday, June 23, the S.S. Tunisian docked at the port of Quebec City on a clear, warm day with a slight breeze to cool the young travellers as they disembarked.

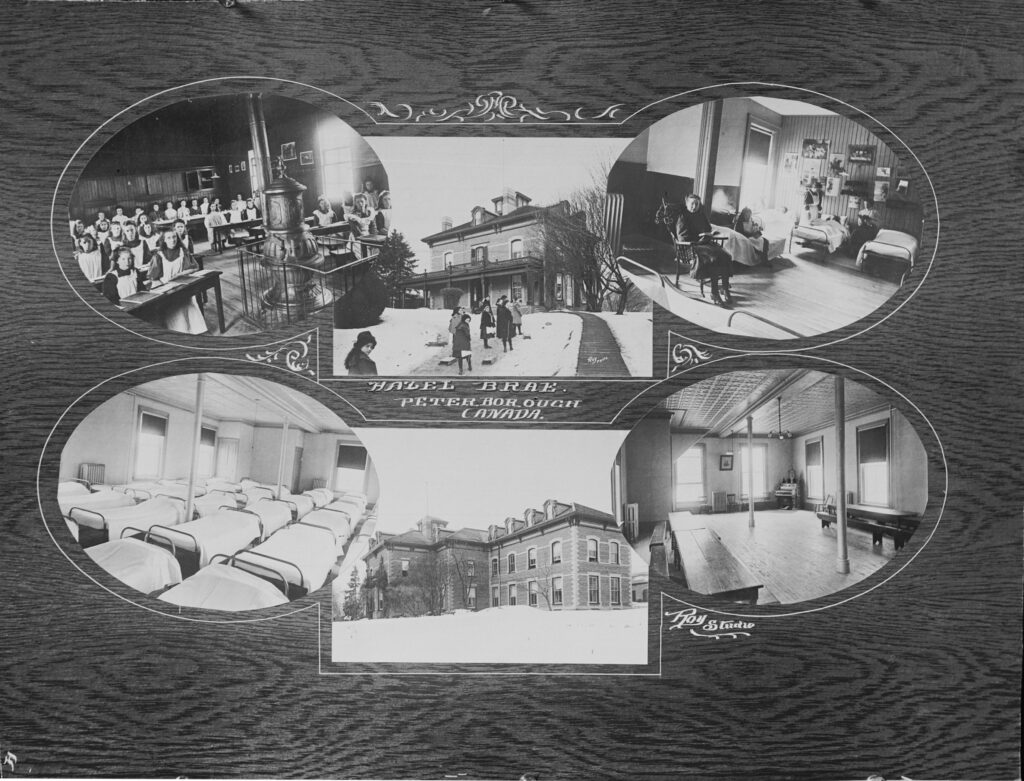

Not yet at their final destination, the girls were herded onto an overnight train bound for Peterborough, Ontario, a city of more than 18,000 people located 100 kilometres northeast of Toronto. Alighting from the train the following day, everyone, exhausted, trekked a short distance up a hill to a driveway that swept in front of a grand, three-storey ivy-covered home with a front verandah spanning the length of the house, and another verandah with walk-outs from the second floor. This was the Distributing Home, also known as Hazelbrae Home (later the Margaret Cox Home), their temporary abode before being shunted off to various parts of the country.

Upon arrival, each girl was assigned an iron bed in the dormitory, arranged headboard to footboard with only a couple of feet to maneouver between the rows. They changed into the fresh uniforms provided to them; high-necked dresses with fuller sleeves, nipped into the waist with the help of a mandatory corset, skirt billowing near the ankles, and layered with a light-coloured pinafore apron that only exposed the collar and sleeves of the dress to help protect it from messes. Young teenagers wore their hair softly pulled back from the face and plaited or curled while older teenagers styled their hair in an up-do.

The girls were given time to acclimate to Canada, emotionally, physically, and culturally, while being taught how to conduct themselves in their new homes. They were highly sought after. There were many more applications than there were girls available. These requests for girls had to include information about the family’s financial, religious, and personal situation, along with a reference letter from either a magistrate or a member of the clergy. Much reliance was placed on the reference letter because homes were not checked for suitability before a girl was sent, and inspection visits to check on their welfare were only scheduled annually. British Home girls were extremely vulnerable, subject to unwanted attention by the men living in and near the home, especially those who were placed on farms, isolated from any neighbours nearby. In addition, not all girls were accepted as part of the family, rather, they were only recognized as labourers or employees and thus subject to firings and “returns”.

Before they agreed to emigrate, Elizabeth and Emily were likely promised that they would be able to remain together once they landed in Canada, giving them a measure of comfort and safety. However, after their arrival at Hazelbrae the sisters were distributed to towns over 50 kilometres away from each other. Communications between the two would have been difficult.

Elizabeth was sent to the town of Dunnville, a small southern Ontario community of less than 3000, located on the Grand River which empties a few kilometres south into Lake Erie. Elizabeth was a petite teenager who wore her thick brunette hair pulled back into a soft bun, with strands that had broken free framing her face. Her facial expression was world-weary yet with a slight smile, and her demeanor was as if she had been taught to be quiet and unobtrusive, to fade into the background. Dunnville was where she eventually met her husband, Alfred Nelson, a plumber who had enlisted in 1916 as part of the war effort. They married in June of that year and Alfred was mobilized soon after, not returning until February 1919. Their first daughter was by then two years old and they added three sons and two more daughters to their family. After nearly 40 years of marriage, Alfred passed away of a heart attack. Elizabeth joined him in death three years later in 1959.

Emily’s life trajectory was decidedly different. Emily was a diminutive young teenager with attractive features, rosy cheeks, hazel eyes, and thick, slightly wavy, dark brown hair. The Barnardo organization placed her in Hamilton, a city on the western tip of Lake Ontario, to work as a housemaid for a young doctor, his wife, and their two small children. She faithfully performed her domestic duties for two years before being returned to Hazelbrae for reasons unknown, although Hazelbrae’s superintendent claimed that Emily was “cunning and sly and very fond of men.” While the following situation may not have occurred with Emily, there is evidence, as mentioned previously, that British Home girls were vulnerable to unwanted advances by men in (or outside) the home where they were assigned. These circumstances could result in the removal of the girl back to the Distributing Home for upsetting the family dynamic. Rarely were the men found to be at fault; blame was solely on the child. Shortly after her return to Hazelbrae in Peterborough, Emily was sent back again to Hamilton, this time to work as a domestic for an elderly couple, their son, and the wife’s elderly sister, while the father and son both laboured 55 hours per week at Hamilton’s Chipman-Holton Knitting Company. The family, frustrated with Emily because the work was too strenuous for her slight five foot frame, returned her to Hazelbrae after one year. This was not an unusual occurence for British Home Children to be repeatedly returned from homes where they were placed. Employers over time became dissatisfied with the child’s labours, or behaviours, and sent them back to the Distributing Homes, sometimes concurrently requesting a more “suitable” child. When she agreed to emigrate to Canada, Emily had not envisioned nor had been promised this type of life. The purported intent of the British Home Child scheme was to integrate the child into a loving, moral family, to have a support system, to get an education, to experience and live a better life. Instead, Emily was working as a domestic servant, being dispatched, sight unseen, to various families far distances from Hazelbrae, with virtually no recourse if the family was unsuitable, and even worse, she had been wrenched away from her sister, the only person who loved and cared for her. Soon after being returned to Hazelbrae yet again, Emily suddenly disappeared.

During the Christmas season of 1915, Emily, using the alias of Johnson, was arrested and charged with vagrancy and prostitution in the town of Belleville, a city located over 100 kilometres southeast of Peterborough. The official wording for the moral crime was “unlawfully was a vagrant being a common prostitute wandering in the public streets and did not give a satisfactory account of herself,” a catch-all “crime” that allowed great latitude for police to arrest women for virtually whatever reason they saw fit, regardless of whether the woman was a sex worker or not. At the time of her arrest, Emily had been living as the common-law wife of a soldier who had not yet been deployed to the war overseas. Emily protested to the constables and claimed the soldier had promised to marry her. The soldier was interviewed and did not deny the relationship, but at the same time he did not have the gallantry to support or defend her. Deference seemed to have been given to soldiers who were on their way to war and unlike Emily, he was not charged with any crime. (His battalion was deployed a few months later and he died of a gun shot wound to the head while in action in France.) Physically and emotionally abandoned by her common-law husband, and as an unmarried woman having few options or resources, a bewildered Emily pled guilty to the charge. She was sentenced by the police magistrate to serve a term of between 6 and 24 months in Toronto’s Andrew Mercer Reformatory for Females, and to be incarcerated in the Belleville jail while she awaited her transfer.

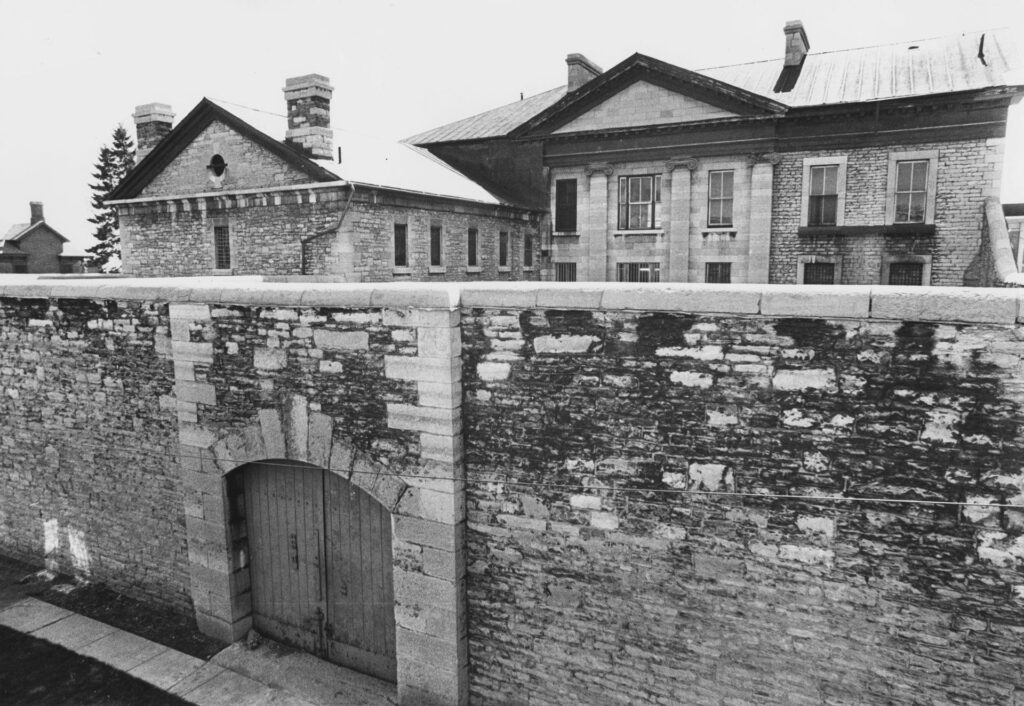

Emily was escorted the few steps from the courtroom to the old stone Belleville jail, which backed onto the courthouse. Built in 1838, it had not been substantially updated over the years. Her surroundings for the next month were as bleak as her mood. The courtyard was compact, butted up against a two-storey stone wall with heavy wooden double doors to allow entrance and exit to the jail. At any given time, a few dozen individuals were incarcerated but very few were women. In fact, that year, only nine women had been imprisoned. However, like Emily, six were transferred to the Mercer, a women’s reformatory where purportedly inmates learned skills to help them gain employment once they were released, although it was fundamentally a prison. After one long month of winter incarceration in the damp, raw Belleville jail, staring at the stone walls and metal cell door, unable to venture outside into the courtyard due to the freezing temperatures, and wondering how her life devolved to this point, Emily, accompanied by Mrs. Scott, a provincial bailiff, was transported via rail on the 200 kilometre trip west along Lake Ontario’s north shore to Toronto to begin her sentence in the Mercer.

A frigid, blustery February day greeted the passengers arriving at Toronto’s rail stop at the Exhibition grounds fronting on Lake Ontario. Temporarily named Exhibition Camp, the grounds were adapted for active training and housing the military during World War One. “Exhibition” was the key word, because tourists were allowed to observe as the military ran drills.

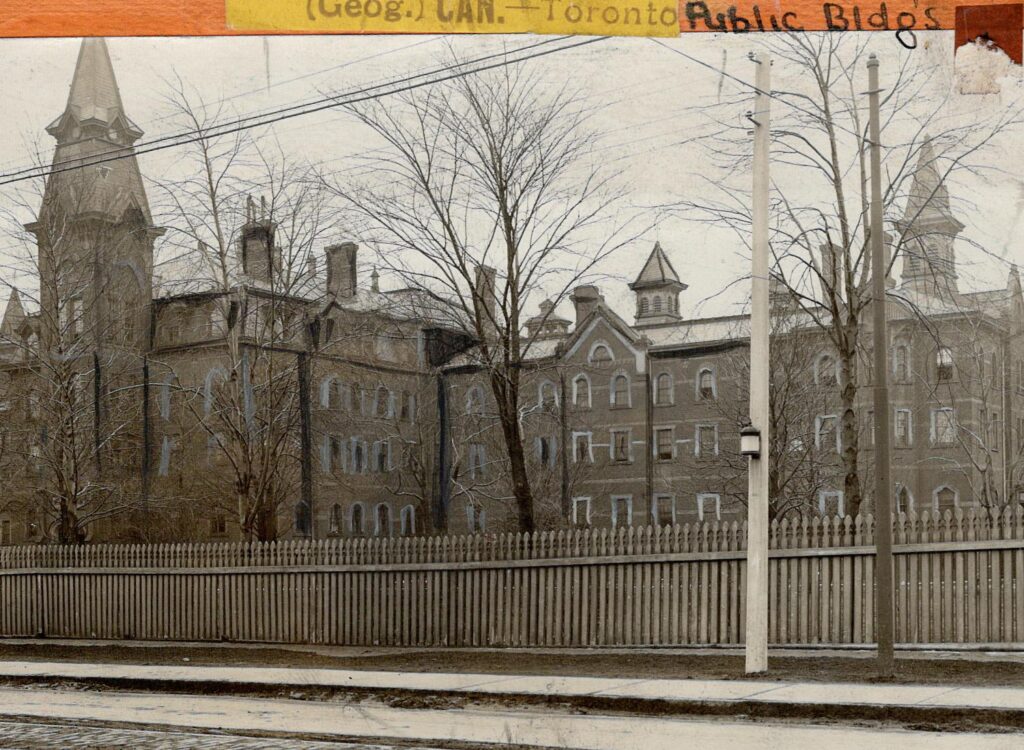

A couple of short blocks to the north on King Street was the Mercer, an intimidatingly massive institution situated on nine acres of land. An impressive tower 27 metres tall greeted both visitors and inmates alike, serving as the main entrance to the Gothic Revival red-brick building. Three storey wings spread symmetrically to the east and west, and an attached structure extended south from the centre block in a T formation, containing workshops and the laundry and drying rooms.

Outside the Mercer, snow flurries swirled about Emily’s thin frame, swathed in a coat unable to adequately insulate her from the inclement weather. To the left of the main stone staircase and tucked in slightly to the back was the entry for inmates. Staff ushered Emily and Mrs. Scott up the narrow stairs and into the receiving area to begin the admission procedure. Once ensconced inside, paperwork was exchanged and custody of Emily “Johnson” was transferred from the bailiff to the matron of the Mercer. As this was a reformatory, Emily was relieved of her clothing and belongings and provided with new undergarments (including a corset) and a uniform, along with a book of rules to govern conduct while incarcerated. Clothed in prison garb and armed with her rules book, Emily was led into the corridor, deeper into the building, and then turned left to the sixteen receiving cells located in the east wing, to her temporary home.

To instil a proper work ethic and control movement of the inmates, Mercer’s daily schedule was strictly regulated and communicated by the sound of gongs.

6:30 Rising

7:00 Unlocking of the cells

7:15 Chapel

7:30 Breakfast

8:00 At place of work

12:00 Dinner

12:30 Recreation

13:00 At place of work

17:00 Supper

17:30 Recreation

18:30 Return to corridors

20:00 Lights out

While incarcerated, each inmate was expected to labour, for free, at cleaning, kitchen duty, doing laundry, or other necessities directed by the staff. However, due to World War One, Ontario legislators formed Mercer Industries which created new work opportunities for the women. A factory was set up, likely on the ground floor where the workshops were located, replete with sewing machines and related equipment dedicated to supplying necessary items for the war effort. Although it was situated in the reformatory, the factory was overseen by an appointee of the Provincial Secretary’s department who took note of the prisoner’s abilities and conduct, observations which were then shared with the Matron.

Emily, for her part, was first tasked with housework, a skill with which she was very familiar given she had been trained as a domestic servant. She was later transferred to the laundry area, although her slight frame and size was a disadvantage due to the mountain of sheets and clothing to be washed and then transported up a flight of stairs to the drying room. Ultimately, her hand was burned after being caught in the ironer. Next, she was given a try in the Mercer Industries factory, however, her abilities and skill level were not a good fit and she was moved back into housekeeping.

Just barely an adult and having had to fend for herself for years, Emily was not fond of authority and found the Mercer’s rigid structure too confining. She was disciplined on practically a monthly basis for minor infractions such as gossiping, whistling and calling to other girls, and having a pencil in her room. Punishments ranged from reprimands, being locked in her cell, or segregated in an isolation/dark cell in the basement, but nothing deterred her from her so-called impertinent and disobedient behaviours. It is possible that she was punished more often than others because after the first few times, the attendents were focussing their attention on her specifically. Emily felt compassion for the other prisoners, which resulted in her being disciplined when she would try to come to their aid. She was once confined to an isolation cell because she attempted to help smuggle a fellow inmate’s letter outside (all mail, incoming and outgoing, was reviewed by Mercer staff who had the sole authority to decide whether the mail would be forwarded or just inserted into the inmate’s file). Frustrated and dejected, Emily attempted to take her life by strangulation. This was met with nonchalance by the Matron who determined that Emily was not serious, rather, she was intending only to attract sympathy from others. Another situation unfolded when Emily was working in the kitchen, located in the basement centre block. Extending both east and west from the kitchen were the punishment corridors housing the 4 by 7 foot isolation cells. Having experienced these dank cells with no light or windows, furnished with only a chamber pot and an iron bed, and restricted to a bread and water diet while smelling the aromas from the kitchen, she felt empathy for those women and tried to secretly pass bread and butter to them. She was caught in the act by the Matron. For her wilfulness, Emily was locked in her cell and placed on a limited diet (bread and water) as punishment. While on rounds, the doctor observed Emily attempting to do violence to herself with her corset-strings and reported the incident to the Matron, who in turn wrote to the Inspector of Prisons complaining that Emily gave a good deal of trouble to the staff. Whenever she was punished she made efforts to injure herself and while she seemed intelligent she was a liar. Emily was temporarily moved to a dormitory on the second floor where she could be watched over by the attendants. Chastened, she became passive, but not for long. She continued to be defiant and insubordinate, if not more so than before, and punishments ensued. Emily knew that her sentence was for no more than two years less a day and she could just wait it out.

After 23 months of incarceration, Emily was paroled on the proviso that she work as a domestic servant for a Mercer-designated family in Toronto at the salary of $15 per month. She left that position after one year for a job at Eaton’s department store at $10 per week, a substantial raise in pay and far more autonomy. Unfortunately, six months after embarking on her new career she became pregnant and had to resign from Eaton’s. Unbeknownst to Emily, Mercer’s administration kept track of former inmates. Mrs. Scott, who was Mercer’s field officer and the same woman who accompanied Emily from the Belleville jail, consulted with Social Service Workers in Toronto to investigate the situation. Emily was found to be homeless after being evicted by her landlady due to fighting with another tenant. Rather than be arrested for vagrancy again, Emily was given the option to be admitted to the Haven. Officially known as The Prison Gate Mission and the Haven, it was a Women’s Christian Association institution located in a residential neighbourhood at 320 Seaton Street that housed, primarily, unwed mothers.

At the Haven, Emily gave birth to a child who suffered from polio and was transferred to Toronto’s Hospital for Incurable Children. Devastated, Emily remained at the Haven for over a year, then eloped for a week before returning. During that week she had become pregnant, resulting in the birth of a stillborn child.

During her stay at the Haven she gained a reputation among staff as being an instigator of trouble. Neighbours complained that Emily stood nude at the windows and moved about in a vulgar fashion. When reprimanded by the staff, she would cry, apologize, and threaten suicide. One day at a meal she spoke under her breath about the quality of the food but the Matron overheard her, which led to Emily being locked in the bathroom. Police were summoned and she was arrested on a charge of incorrigibility.

Emily was taken to the Toronto Women’s Police Court located in Toronto’s City Hall. This court was established in 1913 as a safe environment for female offenders and victims with no men allowed except for the magistrate and lawyers, along with any other male court staff. It dealt with summary convictions, or petty crimes, aimed at providing opportunities for the reformation and redemption of women rather than punishment. In May of 1922, Dr. Margaret Patterson permanently replaced Colonel George Taylor Denison as the first woman police magistrate in Eastern Canada, although she had no legal training when she was appointed. Her background was as a medical missionary in Allahabad, India. Five months into her tenure as magistrate, she was presented with Emily’s case. Magistrate Patterson, after hearing from all involved and the history of Emily, amended the charge to vagrancy, a sentence which could not exceed six months, rather than incorrigibility, a term not to exceed five years. Remanded to jail for one week, two male doctors examined Emily to determine if she could be certified insane under the Hospitals for the Insane Act. Their notes stated she had “delusions of persecution”, “had been abused and put upon”, and that she “looks defective.” Emily was committed to the Ontario Hospital, Toronto (formerly known as the Provincial Lunatic Asylum) in October 1922.

The Ontario Hospital, Toronto was yet another institution of immense proportions, located just across the street from the Mercer, housing almost five hundred women and over three hundred men at the end of October 1922. Upon admission, Emily was removed to the women’s intake area and bathed while the nurses noted in her file all body marks and scars. Next was a physical examination followed by a psychiatric analysis. Upon completion, one of the psychiatrists wrote in her file:

As far as I can find out, this girl is not hallucinated or delusioned, and she is well oriented. She answers questions readily and her narrative is coherent in every particular. (. . .) When I first saw this girl, she could not tell me who was Mayor of Toronto or the President of the United States, but the next day when I saw her, she had this information readily at hand. She said that the first day I asked her these questions she was nervous and could not think; at any rate she had enough ambition and wit to inform herself in the meantime. (. . .) She has not the appearance or the actions of a vicious or degenerate girl, and I do not think she is very weak minded.

Another psychiatrist a month later concluded “there is very little the matter with this girl. (. . .) I think she could get along outside.” After being institutionalized in the asylum for two-and-a-half months, Emily was noted as being “pleasant and quiet, and one might almost say that her conduct has been in most ways, exemplary.” However, the psychiatrists had a concern regarding her moral history, and that she considered her sexual improprieties and pregnancies as only slight transgressions. “It is difficult to know what to do with a girl like this.”

Moral and reproductive concerns were on the rise post-World War One. Women were particularly vulnerable to these condemnations, especially those who exhibited behaviours such as sex outside of marriage or were unwed mothers. Ideas to reduce these immoral activities were to either sterilize the woman or segregate her from society. Ontario chose the segregation (institutionalization) route. Part of the reasoning was that if a woman was sterilized, it just meant she wouldn’t get pregnant. There were no consequences to stop the woman from having sexual intercourse at will, and she may spread venereal disease. So, what to do with an attractive, resourceful, young woman like Emily who was not exhibiting any signs of mental illness? The psychiatrists at Ontario Hospital, Toronto decided to transfer her, along with few dozen “quieter” female patients who were in good health, to the Ontario Hospital, Cobourg (formerly the Cobourg Asylum for the Insane) in February 1923, keeping her institutionalized indefinitely as there were no laws that said she had to be released on a specific date, or at all.

The women, ranging in age between 22 and 69, along with their meagre belongings, were assembled at the nearby Exhibition grounds train station. Everyone was bundled into boots, coats, and hats as insulation from the biting winds blowing off the lake. Along with a few female chaperones, they carefully ascended the few steps onto the train to be transferred to the Ontario Hospital, Cobourg, located over 100 kilometres east in a small town on Lake Ontario’s north shore. Temperatures were hovering just below freezing and a light snow was floating down with barely a wind when the patients arrived hours later in Cobourg, chilled and uneasy. They were transported en masse from the train station and driven up the snow-covered hill to their new home. This psychiatric hospital was more humble in size than the Ontario Hospital, Toronto, housing slightly less than 400 women, but had an air of sophistication with its light-coloured brick and symmetrical wings running parallel to the road. Four neoclassical columns, each three stories high, flanked the outdoor centre stairway, and a prominent cupola graced the centre roof. Its aesthetics did not feel as intimidating and institutional, perhaps because the building was originally erected in the mid-1800s as an educational academy, later to become Victoria College University until it merged with the University of Toronto and it’s doors closed to academia in 1892. A decade later, the Cobourg Asylum for the Insane was inaugurated as the province’s sole women-only facility. (All asylums in 1919 were renamed Ontario Hospitals to help remove the “asylum” stigma.)

Less than two months after her transfer, the Cobourg psychiatrists noted that Emily was quiet, in good physical health, and easily managed. “On taking into consideration this patient’s previous history and the general appearance of the patient, there is little or no doubt but that this is a case of High Grade Imbecility.” Two days after this notation in her file, Emily escaped from the Cobourg asylum with the pre-arranged assistance from one of the nurses. The nurse had been communicating with a boyfriend of Emily’s and had arranged for Emily to be at a particular location in downtown Cobourg on a specific evening. She asked her supervisor for a written order to take a patient out, but her request was denied. Disregarding the refusal, the nurse absconded with an anxious, yet eager Emily to where the friend was waiting in a vehicle. During this time, the night nurse noticed Emily was missing from the ward and reported it to the Night Supervisor. Police and staff at railway stations were immediately notified and provided with Emily’s description, but she had already vanished. The nurse who had assisted in the escape “was relieved from duty, turned in her keys and uniforms, and is no longer a member of the nursing staff.”

After being absent for over thirty days, Emily was written off as an eloper (escaper) and the staff at Ontario Hospital, Cobourg received a Warrant of Discharge for her from the Office of the Inspector of Prisons and Public Charities, Ontario.

Where did Emily go? She successfully disappeared. Emily may have changed her name as she had before, and perhaps even fled the country to the United States. She likely had not been in contact with her sister Elizabeth for years, if not decades, because there was no mention of her in Elizabeth’s obituary, nor were there any mentions of Elizabeth in Emily’s case files. However, there is a post-script to this story. A memorial to the British Home Children who passed through Hazelbrae has been erected at the Queen Alexandra Community Centre at 180 Barnardo Avenue in Peterborough. The names of the 8914 children, mostly girls, are inscribed on its face, including the names of Emily Metcalf and her sister Elizabeth, never to be forgotten.